Breaking the Silence on Impostor Syndrome

A Conversation with Counselor and Researcher Whitney White

Impostor syndrome—it’s a phrase that many professionals, including counselors, are intimately familiar with. The persistent feeling of self-doubt, the fear of being exposed as a "fraud," even in the face of overwhelming evidence of competence, is something that plagues individuals across various fields. But what happens when a counselor, someone trained in self-awareness and emotional intelligence, experiences it?

In this candid interview, Whitney White, a counselor based in Tennessee and a PhD student researching impostor syndrome, opens up about her journey, her struggles, and her research into this deeply personal and widely experienced phenomenon. From her early steps into the counseling profession to her rigorous PhD program, Whitney shares her insights into impostor syndrome, the challenges of academia, and how counselors can navigate feelings of doubt while helping others.

A Counselor’s Journey: Finding Her Calling

Whitney’s path to counseling was not entirely linear. Like many psychology undergraduates, she found herself at a crossroads after earning her bachelor's degree, unsure of her next step. Taking a year off gave her the space she needed to reevaluate her future.

“I felt really stuck during that time,” Whitney recalls. “I was in a job I didn’t enjoy, and I kept thinking, ‘I should be doing more.’”

That word—should—a common red flag of self-imposed pressure, would later become a central theme in her understanding of impostor syndrome. Eventually, counseling presented itself as the right path, aligning with her passion for helping others.

Coming from a family of helpers, including a mother in law enforcement, Whitney always had an inclination to support and guide people. Once she entered her master’s program in counseling, everything clicked. For the first time in her academic career, she excelled. “I realized that I loved it, and it was obvious that this was the right field for me,” she says.

The Leap to a PhD: More Than Just a Degree

While many counselors build their careers in clinical practice, Whitney felt drawn to academia. Transitioning straight from her master’s program into a PhD in Counselor Education and Supervision, she quickly learned that doctoral studies were a completely different ball game.

“This has been one of the most humbling experiences of my life,” she admits. “I went from feeling competent in my master’s program to suddenly feeling like a beginner all over again.”

The PhD program, particularly the shift from clinical work to academic research, pushed Whitney out of her comfort zone. Writing at a doctoral level, designing a research study, and preparing a dissertation presented new challenges, reinforcing her own experience with impostor syndrome.

“I had to learn how to take constant feedback without internalizing it as a personal failure,” she says. “It’s a completely different skill set, and there were moments where I questioned if I belonged here.”

Why Study Impostor Syndrome? A Personal Connection

Whitney’s decision to research impostor syndrome wasn’t a pre-planned passion—it was a topic she stumbled upon in a moment of vulnerability.

“I initially proposed a different research topic, but I felt completely out of my depth,” she confesses.

“I was experiencing impostor syndrome in real-time.”

Her mentor recognized this and suggested she explore the topic academically. Whitney dove into existing research and quickly realized its relevance—not just to her, but to the counseling field at large.

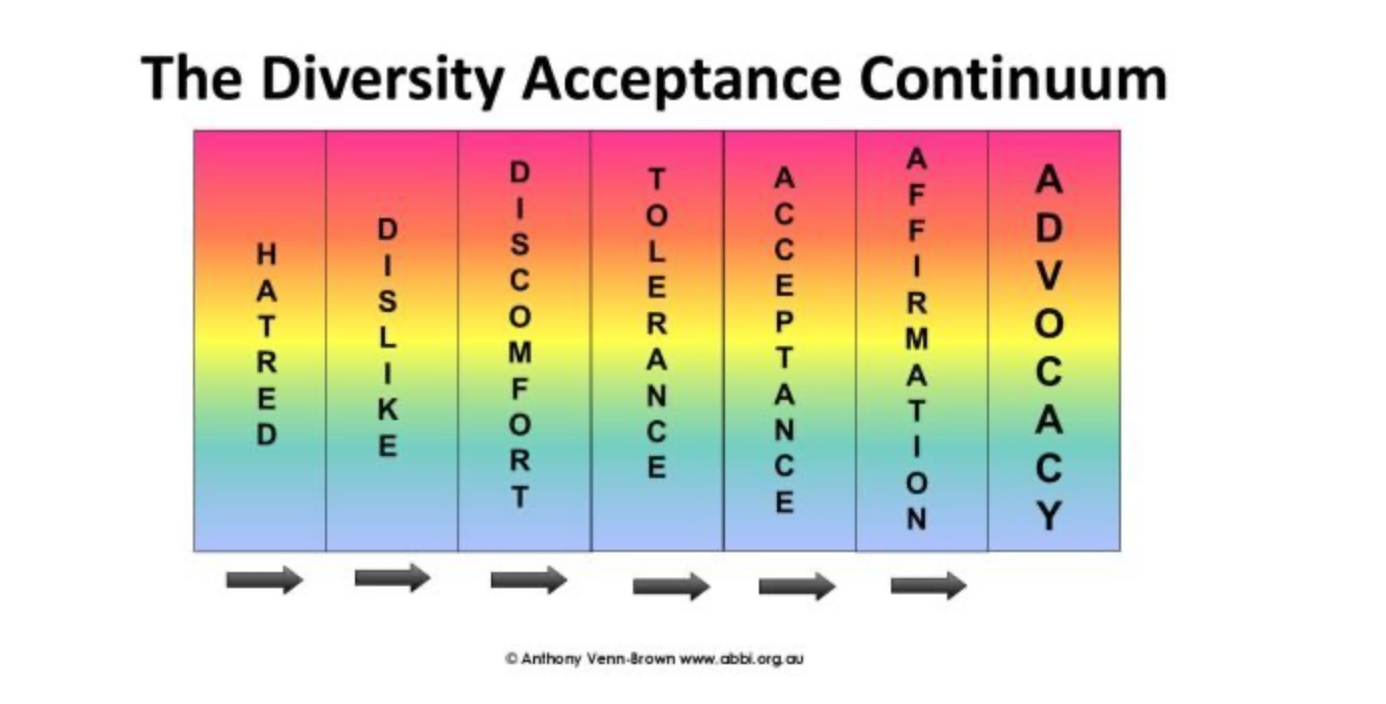

Impostor syndrome, or impostor phenomenon, is characterized by persistent self-doubt and the inability to internalize achievements, despite clear evidence of competence. Whitney’s research focuses on how self-concept influences impostor syndrome among clinical counselor supervisors—a gap she identified in the literature.

“There’s been a lot of research on how mindfulness can mitigate impostor syndrome,” she explains. “But self-concept—how we see ourselves in various roles—hadn’t been deeply explored in relation to impostor phenomenon.”

Her study examines whether factors like age, gender, and years of supervisory experience impact the relationship between self-concept and impostor syndrome. Interestingly, preliminary findings suggest that impostor syndrome doesn’t discriminate—it can affect anyone, regardless of experience level.

The Counseling Profession and Impostor Syndrome: A Perfect Storm?

The counseling profession demands a high level of self-awareness, emotional intelligence, and boundary setting—all while holding space for the deep struggles of others. This, Whitney believes, might create an environment where impostor syndrome thrives.

“As counselors, we are trained to be highly reflective and self-aware,” she says. “But that same self-awareness can turn into self-doubt. We might think, ‘I should know better than this,’ or ‘Why am I struggling with my own emotions when I’m supposed to be helping others?’”

Furthermore, because rapport-building and empathy often come naturally to counselors, some may feel that their success isn’t due to skill or training but rather just who they are—a classic hallmark of impostor syndrome.

David, the interviewer, poses an interesting question: “Does the counseling profession itself lend to impostor syndrome?” It’s an area of research that Whitney believes could be worth exploring further.

Strategies for Overcoming Impostor Syndrome

So, how can counselors (or anyone) combat impostor syndrome? Whitney offers several strategies:

- Fact-Checking Your Thoughts

- “When someone experiences impostor syndrome, I ask them: What evidence do you have that supports this belief? And what evidence contradicts it?”

- More often than not, the evidence shows competence, not fraudulence.

- Recognizing that Opportunities Come from Merit, Not Luck

- “The opportunity wouldn’t be there if you weren’t qualified,” Whitney emphasizes. “You didn’t just ‘get lucky’—someone evaluated your experience and decided you were capable.”

- Normalizing the Experience

- Impostor syndrome affects highly accomplished individuals, from CEOs to doctors to therapists. “You’re not alone,” Whitney reminds us. “Many people feel this way, even those you look up to.”

- Seeking Support and Mentorship

- “Having a mentor or support system can help you see yourself more clearly,” she says. “Sometimes, we need others to remind us of our worth.”

What’s Next for Whitney?

With her dissertation nearing completion, Whitney anticipates finishing her PhD by September. After that, she hopes to balance private practice with a role in counselor education.

“My dream is to continue working with clients but also to start teaching,” she shares. “I love interacting with students, and I want to help train the next generation of counselors.”

As for a book? Maybe. “We’ll see what happens,” she laughs, acknowledging that her journey is still unfolding.

Final Thoughts: Advice for Aspiring PhD Students

For those considering a PhD in Counselor Education and Supervision, Whitney offers some practical advice:

- Do Your Research – “Not all PhD programs are created equal. Find one that aligns with your career goals.”

- Read Dissertations – “Look at what past students have written. It gives you an idea of what to expect.”

- Be Ready for Humility – “A PhD is humbling. But it also teaches you resilience.”

Conclusion

Whitney White’s journey highlights the paradox of impostor syndrome: the people who experience it are often the ones who care the most, work the hardest, and are the most competent. By breaking the silence on impostor phenomenon in the counseling profession, she’s not only contributing valuable research but also normalizing an experience that so many face.

If you’re in Tennessee and seeking a skilled therapist who truly understands the weight of self-doubt, you can find Whitney on Psychology Today or connect with her on LinkedIn.

And if you’ve ever struggled with impostor syndrome yourself, take Whitney’s advice to heart:

You are more qualified than you think. The opportunity wouldn’t be there if you weren’t meant for it.