The Landscape of Counseling in South Africa

An Interview with Eduan Greyling

South Africa’s mental health sector is evolving, with increasing awareness of the importance of counseling and therapy. While access to counseling services continues to expand, both challenges and opportunities define the profession. I recently sat down with Eduan Greyling, a professional counselor based in Cape Town, to discuss his journey into the field, the regulatory landscape, and the nuances of counseling in South Africa.

I discovered Eduan through the Psychology Today website and reached out to request an interview. He was one of three counselors I contacted and the first to respond. Aware of Cape Town’s rich cultural diversity, I aimed to interview counselors from different racial and ethnic backgrounds as well. However, the others I reached out to did not respond. I plan to follow up again soon in hopes of capturing a broader range of perspectives on counseling within South Africa’s beautifully diverse cultural landscape.

The Evolution of Counseling in South Africa

The counseling profession in South Africa has evolved significantly, shaped by historical contexts and current societal needs. Historically, counseling psychology in South Africa was primarily concerned with serving the goals of the nationalist government and addressing the needs of the minority White Afrikaans-speaking citizens of the country. This focus on vocational issues and health promotion in the development of counseling psychology in South Africa mirrors the evolution of the specialty in the United States.

To practice as a counseling psychologist in South Africa, individuals must register with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA). Prerequisites include completing a four-year degree in psychology, an accredited master's degree in counseling psychology, a one-year internship, and passing the Board Examination.

Registered counselors, distinct from counseling psychologists, are trained to provide a variety of psychosocial interventions to individuals, groups, and communities. These may include prevention and health promotion initiatives, psychoeducation, short-term supportive counseling, and psychological assessments. They work in various settings, including NGOs, correctional services, district hospitals, schools, and community programs.

Building a Counseling Practice in Cape Town

Starting a private counseling practice, particularly as a young professional, came with its fair share of skepticism. “People told me I was too young, that I didn’t have enough wisdom,” Eduan recalls. “But passion is what drives success. I had to push through the doubts and build my practice step by step.”

One of the key challenges in South Africa is the financial barrier to accessing mental health services. While some counselors are affiliated with medical aid schemes, many clients still pay out-of-pocket. “Counseling is often seen as a luxury,” Eduan admits. To make therapy more accessible, he offers pro bono sessions and discounted rates for lower-income clients. In fact, Eduan offers three pro-bono sessions each week on Wednesday mornings, available on a first-come, first-served basis. This innovative approach makes counseling more accessible to individuals who might otherwise be unable to afford it due to financial constraints.

Referrals have played a significant role in growing his practice. “Word of mouth is your best friend,” he emphasizes. “It’s about building trust and delivering results.”

Practical Training and Real-World Experience

Eduan points out a significant gap between university education and the realities of counseling. “My degree gave me a solid theoretical foundation, but it didn’t prepare me practically,” he admits. “I learned everything once I started working.”

For him, hands-on experience came through volunteering with an NGO, where he was mentored and supervised. “The biggest skills I learned were reading body language and active listening. You have to train yourself not to formulate responses in your head before your client has finished speaking.”

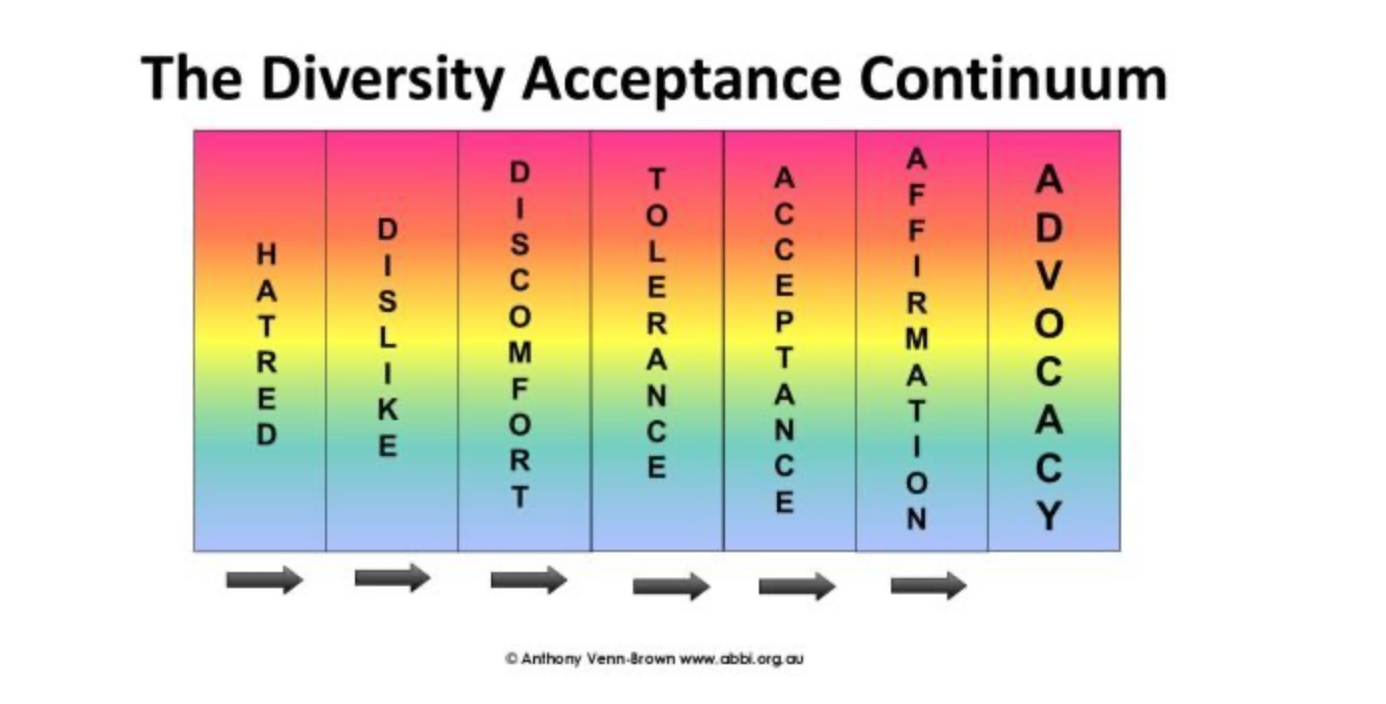

Diversity and Accessibility in Counseling

A common misconception about counseling in South Africa is that it is only accessible to white, upper-class clients. Eduan’s practice, however, serves a diverse client base, including Black, Indian, and Coloured individuals from various socioeconomic backgrounds.

“I have clients from different racial and economic backgrounds, which is a sign of progress,” he says. “But the reality is that private counseling still remains inaccessible to many.”

Despite the growing recognition of mental health's importance, challenges persist. The integration of counseling psychologists into the South African public health system has been an ongoing point of contestation. At present, the state mental health system only has posts for clinical psychologists, although this was not always the case. In 1996, the number of counseling psychologists in full-time state employment was significantly larger than the number of clinical psychologists. However, recent data show that the range of employment options for counseling psychologists outside of private practice and higher education is limited. Currently, almost half of all counseling psychologists work in private practice, a setting that excludes the economically marginalized, mostly Black residents of the country.

Ethics and Boundaries in Counseling

Maintaining professional boundaries is crucial in therapy. When asked about working with clients whose values or lifestyles may differ from his own, Eduan is clear: “Counseling is about helping people, not judging them. You have to bracket your personal beliefs and provide support within your scope of practice.”

Counselors in South Africa must follow strict ethical guidelines set by their regulatory bodies. If a client believes a counselor has breached confidentiality, they can file a complaint with the HPCSA or another governing organization. “There are systems in place to protect clients, and that’s important for accountability,” he says.

Final Thoughts

Eduan’s journey illustrates both the potential and the challenges of working as a counselor in South Africa. While financial constraints and accessibility issues persist, the profession is growing, and more people are recognizing the value of mental health support. With dedicated professionals like Eduan leading the way, the future of counseling in South Africa looks promising.

Professional organizations, such as the South African Association for Counselors, play a pivotal role in promoting and advocating for the counseling profession. They offer membership benefits, professional development, and networking opportunities to support counselors throughout their careers.

For more information on Eduan’s practice, visit his website here.